Conni counters: a look at copyright and trademark law

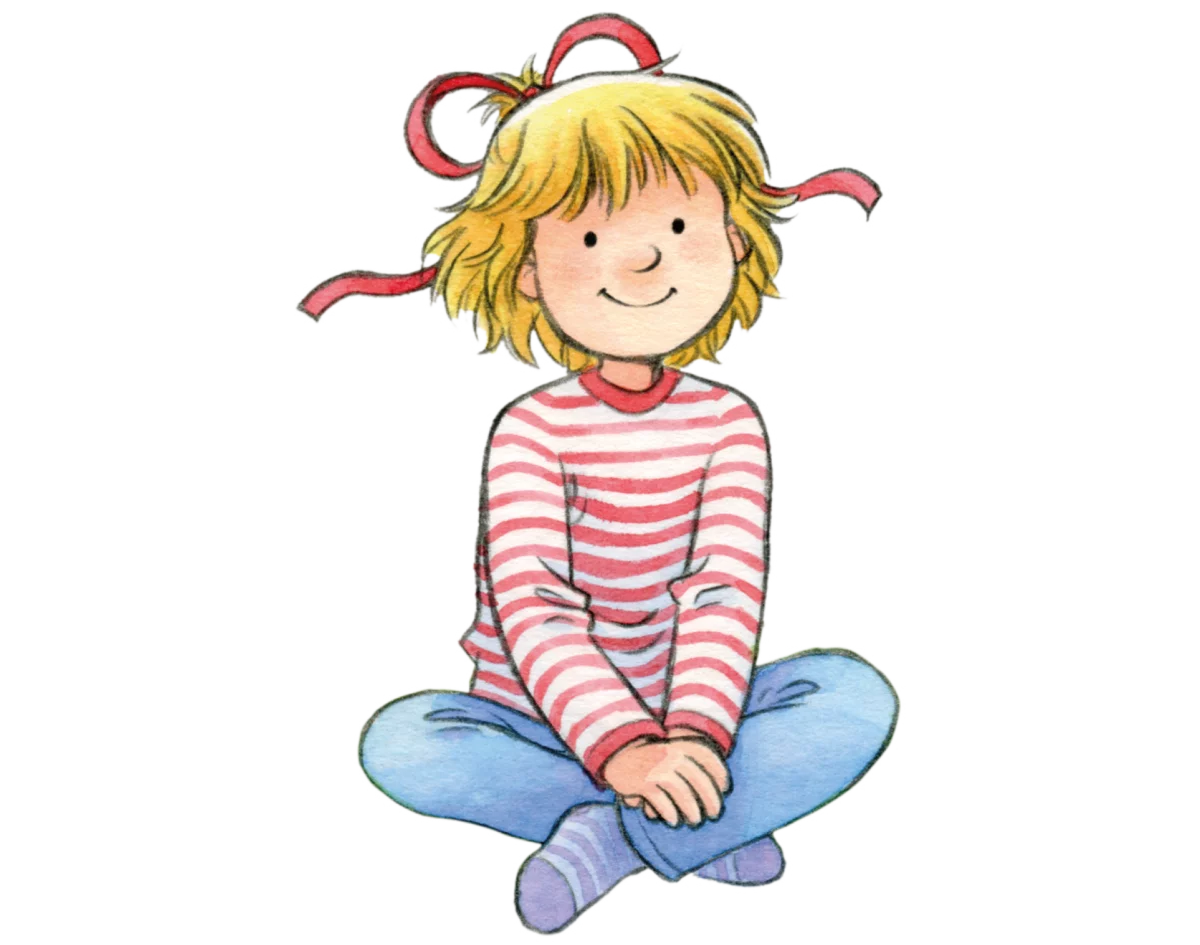

Picture: WDR Media Group

The Conni books from the Carlsen publishing house are probably very well known and popular in many German children’s rooms. Many readers who occasionally visit the internet will therefore be familiar with the “Conni meme”.

For the uninitiated: The Conni books are a series of short stories in “Pixi book” format, i.e. small, 24-page picture booklets for children. The striking cover pictures of the series show the blonde, red-cheeked girl in a striped shirt in various everyday situations. The titles follow a certain pattern. They are always descriptive in nature and contain the name of the title character and the central plot of the little booklet (e.g. “Conni celebrates her birthday”, “Conni can’t fall asleep”…).

Internet culture in Germany has adopted this unmistakable conciseness and reinterpreted the cover images as memes. The “meme” is a product of the Internet and is described as a multimedia structure, i.e. mostly humorous images with text, animated GIFs or edited videos.[1] However, their success is not only based on mere imitation; rather, each template is creatively changed and reinterpreted when it is reused. 2] This is also the case with the “Conni memes”: Here, the Conni covers are retitled, photomontaged or created by AI in the Conni style by the meme creators. The “joke” here is to contrast the innocent, ideal world of the “Conniverse” with current political circumstances or social observations. For example, Conni uncovers mask scandals or becomes a BND snoop. Unfortunately, the memes are also used by people with extreme, sometimes inhuman views to convey their messages.

The Carlsen publishing house, owner of the rights to the Conni books, has taken the latter in particular as an opportunity to put an end to such memes. It published a statement on the publisher’s website[3], which emphasizes that the publisher neither allows the Conni works to be used in this way nor grants permission to do so. At the same time, a warning from the publisher’s law firm is to be expected in the event of violations.

The expected outcry in Internet circles was huge. Under buzzwords such as “Conni-Gate” or “Conni Affair”, the publisher was accused of censorship and violations of freedom of expression.

But what is the legal situation? Does Carlsen have a right to prohibit the uses? How far could such a right extend?

Preliminary question: Are figures protected and not just an exact image?

A basic principle of German copyright law is that ideas in themselves are not eligible for protection. Instead, only the concrete elaboration is always the object of copyright protection. Therefore, one could ask whether the abstract representation of the Conni character (also under other names, such as Tonni, Nonni, etc.) is protected by copyright at all without recourse to the original drawings (in particular by means of AI-generated images).

But let us first approach the clearer cases: The titles of the Conni books are only protected as linguistic works under the Copyright Act if they constitute a personal intellectual creation in themselves, which is necessary for the so-called work quality. The Conni titles always follow the same simple pattern: “Conni goes to the dentist”, “Conni goes horse riding”, “Conni does …”. First and foremost, the titles simply describe the content of the book and are also very short. Such titles are too simple to achieve an independent level of creativity.

However, the specific drawings in the books and the covers are protected as works of fine art.

A figure itself can also enjoy copyright protection. In 2013, the Federal Court of Justice ruled that literary figures can be protected as linguistic works.[4] The Federal Court of Justice has long recognized abstract protection for visual representations of figures[5].

The BGH has established the following requirements for this protection: Characters enjoy protection “if they are characterized by an unmistakable combination of external features, character traits, abilities and typical behaviour, are thus formed into particularly distinctive personalities and appear in the stories in a certain characteristic way.”

In the case of Conni, it is easy to assume that she has the unmistakable combination of external features (white and red striped shirt, red bow…), a distinct personality and certain character traits (childlike, optimistic behavior…). Conni also always appears in the works in this particular characteristic manner. [6]

Infringement according to the UrhG

The Conni character is therefore protected by copyright. In order for the rights holders to be able to take legal action against the meme creators, the creation and posting of the Conni memes would have to constitute legally relevant acts of infringement.

There are several versions of the Conni meme. In some cases, an existing original Conni cover is simply given a different title. Posting the unedited cover image is an act of reproduction and distribution, which are reserved solely for the rights holder.

Other versions of the Conni meme use a Conni cover edited by photomontage. This represents an adaptation and redesign of a work. Their publication and utilization is subject to the consent of the rights holder.

Finally, the use of generative artificial intelligence is popular with Conni meme creators. This makes it possible to create covers based on the Conni covers without much effort, in which the character “Conni” is still recognizable. The use of AI-generated images in which Conni is clearly recognizable would also require the permission of the rights holders.

Processing permitted by way of exception

Copyright law provides for an exception for adaptations that are sufficiently different from the original. However, the Conni memes cannot be regarded as such. For this to be the case, the memes would have to be so far removed from the original that the elements of the original work that justify protection would no longer be recognizable.[7] However, the purpose of the Conni memes (and memes in general) is precisely the recognizability of the parodied source information. This is why AI-generated Connis with slight visual deviations or slightly renamed Tonnis, Nonnis or similar variants are still to be regarded as non-free adaptations. This is because the original Conni is still recognizable, which is probably the intention of the creators. In addition, the memes themselves would have to achieve work quality, which will not be the case with AI-generated images and simple retitling.

Main question: Parody vs. distortion

Copyright law also contains further exceptions to exclusivity. In particular, there is permission to reproduce, distribute and publicly communicate a published work for the purposes of caricature, parody and pastiche. If the Conni memes pursue one of these purposes, the creators could rely on this and would therefore not need permission from Carlsen-Verlag to create and publish the memes. In contrast to a free adaptation, it is also irrelevant whether the caricature, parody or pastiche itself constitutes a copyright-protected work, so that the AI-Connis are not excluded from the outset. [8]

First step: caricature, parody or pastiche?

In order for Conni memes to fall under the permission, they would have to be classified as parody, caricature or pastiche.

While caricature and parody are characterized by humorous or mocking elements, pastiche can also represent a form of recognition of the underlying work.[9] Meanwhile, a clear distinction between parody and caricature is not possible.[10] In contrast to caricature, which is often aimed at people, parody tends to refer more strongly to specific works or types of works.

The European Court of Justice ruled that “the essential characteristics of parody are, on the one hand, to recall an existing work while at the same time showing perceptible differences from it and, on the other hand, to constitute an expression of humor or a mockery. The term ‘parody’ within the meaning of this provision does not depend on the conditions […] that it concerns the original work itself or that it indicates the parodied work.”[12]

Most Conni memes fulfill the basic requirements of a parody. They are reminiscent of an existing work, namely the protected character “Conni”. In order to achieve perceptible differences from the character, it does not necessarily have to be visually altered or renamed. As described above, a character enjoys protection precisely because of her personality and typical behavior. When the character Conni is placed in a new context in memes, they already achieve perceptible differences. Since the recontextualization is what makes the Conni memes so special, every meme should maintain the necessary distance.

In terms of content, the memes must be an expression of humor or mockery in the broadest sense. The requirements for this are not particularly high. The threshold is already reached as soon as an objective observer with the necessary intellectual and cultural understanding recognizes the parody.[13] The entertaining effect of the memes is mainly created by the deliberately chosen contrast between the childlike, naïve appearance of the protagonist and a (partly exaggerated) socially critical commentary. The depiction of a seemingly intact, orderly world – as conveyed by the Conni books – becomes a projection surface for political and/or social issues that make use of this ironic refraction. The meme format is also often used to disapprove of or mock politicians and other important personalities. Even in designs that do not deal with political or socio-critical topics, but rather use humorous elements alone, the focus is always on the pointed comparison. Accordingly, the Conni memes can generally be seen as an expression of humor or mockery.

It is harmless for the classification of the Conni memes that the humorous or mocking depiction does not refer to the character Conni as such, but that the protagonists are merely used as a strategic tool[14].

Accordingly, the Conni memes (like most memes) can generally be categorized as parodies.[15]

Second step: Balancing of interests

When applying the exceptions for caricature, parody and pastiche, a fair balance must always be struck between the rights and interests of the creators and the users’ right to freedom of expression.[16] Therefore, the interests must be weighed up, taking into account all the circumstances of the individual case.[17] Only if the creators’ interest in use outweighs the rights holders’ interest in protection can the former invoke the exception.

The authors of the Conni figure have a legally protected interest in prohibiting distortions and other impairments of their work.

On the part of the meme creators, the courts must also take into account freedom of art and freedom of expression.[18]

Cases can be identified in which the balance of interests will regularly be in favor of the rights holder. Particularly noteworthy are situations in which the meme aims to spread discriminatory statements and extremist world views. In this case, the author has a “legitimate interest in ensuring that the protected work is not associated with such a statement”[19].

In addition to the balancing of interests, the so-called three-step test must be carried out[20].

The first level, according to which restrictions and exceptions may only apply in certain cases, has been fundamentally regulated by the introduction of Section 51 a UrhG. However, the second and third levels are central, which on the one hand stipulate that “normal exploitation” must not be impaired and on the other hand that the author’s legitimate interests must not be unduly infringed. At the third level, the author’s moral interests in particular must be taken into account. [21]

In the case of the Conni memes, no serious problems are recognizable at the second level. The original Conni memes are in no way in competition with the Conni books.[22] It is also not apparent that the Conni books will find fewer buyers on the market just because some disrespectful Conni memes are circulating on the Internet. On the contrary, it is possible that demand for the Conni books is increasing due to the high level of attention generated by the viral memes.

On the other hand, as in the first balancing of interests, idealistic values must be taken into account at level three. The Carlsen publishing house has a legitimate (idealistic) interest in taking action against memes that share and glorify discrimination, violence or extremist content, for example. The publisher does not have to tolerate any association of the works with such views.

Conclusion on the UrhG

As long as the Conni character is not distorted on the Internet and the publisher’s legitimate interests are not infringed as a result, she may continue to appear in memes as a well-known face.

The Carlsen publishing house is legally well advised and has recognized that it can defend itself above all against the inhuman, extremist distortions of the work. In a further statement, Carlsen therefore makes it clear that action will only be taken against such infringements of rights. The outcry on the Internet has now subsided.

Infringement under the MarkenG

In the information published by CARLSEN Verlag on Conni memes, the publisher also invokes an infringement of trademark law in addition to copyright infringement. The publisher has registered the name “Conni” as well as the logo, font and drawings of Conni as trademarks.

Trademark law prohibits third parties, including the Conni meme creators, from taking certain actions in the course of trade in relation to goods or services without the consent of the trademark owner.

A Conni meme can infringe trademark law if it is used in the form of a trademark parody to identify one’s own products. This is because the meme is then aimed at making use of the distinctive character or image of the Conni trademark[23].

In the case of Conni memes, such an infringement can generally only be assumed if a company publishes the meme with a specific reference to the product or service on its company website or the company’s social media channels to promote its own products or services. Without reference to a company and its products and services, a Conni meme cannot infringe trademark law. Conni memes are therefore generally permissible brand names, as the lack of reference to product advertising usually also means that freedom of art and freedom of expression are in dispute as to whether the naming is permissible.

Conclusion on the MarkenG

In the vast majority of cases, the Conni memes do not violate trademark law unless they are advertising a third-party product.

Conclusion

As shown, the creation of memes is covered by legal exceptions in most cases. Conni can therefore continue to be used for satirical debate.

However, a rights holder does not have to tolerate any misuse of their own works. Meme creators should therefore stay away from parodies that glorify violence, are discriminatory or inhumane. And not only because they would then be committing acts of bad taste, but also because legal action would then not be unjustified.

Image: https://licensing.wdr-mediagroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WDR_MG-Marke-Cooni_Illustration-1200×945.png

[1] Nowotny/Reidy, Memes – Formen und Folgen eines Internetphänomens, 2022, p. 11f. [2] Nowotny/Reidy, Memes – Formen und Folgen eines Internetphänomens, 2022,p. 11f.[3] Available here: https://www.carlsen.de/sites/default/files/2025-06/Conni-Memes_FAQ.pdf?srsltid=AfmBOopS3Jclgh2gT2r9mAqhUp8XcObN4ckr6jN8TCbKror1LyexxWar (29.07.25)

[4] BGH, judgment of July 17, 2013 – I ZR 52/12, para. 29 et seq. [5] BGH, judgment of March 11, 1993 – I ZR 263/91, BGHZ 122, 53, 56 f. – Alcolix; judgment of March 11, 1993 – I ZR 264/91, GRUR 1994, 191, 192 – Asterix-Persiflagen; judgment of July 8, 2004 – I ZR 25/02, GRUR 2004, 855, 856 = WRP 2004, 1293 – Hundefigur.[6] This is also the case here https://www.ratgeberrecht.eu/aktuell/conni-memes-und-abmahnungen/ (15.07.2025).

[7] BGH, judgment of. 7.4.2022 – I ZR 222/20 = GRUR 2022, 899. [8] BT-Drs. 19/27426, 90. [9] BT-Drs. 19/27426, 91. [10] Dreier, in: Dreier/Schulze, Urheberrechtsgesetz, 8th ed. 2025, § 51a, marginal no. 9. [11] BT-Drs. 19/27426, 91. [12] ECJ, GRUR 2014, 972, 974. [13] BGH, judgment of March 26, 1971 – I ZR 77/69, GRUR 1971, 588, 589 – Disney-Parodie; BGH, GRUR 1994, 191, 194 – Asterix-Persiflagen.[14] ECJ, GRUR 2014, 972, 974, Lüft/Bullinger, in: Wandtke/Bullinger, Urheberrecht, 6th ed. 2022, para. 12.

[15] See also Raue, “Who let the memes out?”, LTO article of 10.8.22, available at https://www.lto.de/recht/hintergruende/h/memes-zulaessig-urheberrecht-parodie-raue-lto1 (22.7.25)

[16] ECJ, GRUR 2014, 972, 974; BGH, GRUR 2016, 1157, para. 36 et seq.[17] ECJ, GRUR 2014, 972 para. 27 – Deckmyn and Vrijheidsfonds/Vandersteen et al.

[18] Dreier/Schulze/Dreier, 8th ed. 2025, UrhG § 51a Rn. 15.

[19] ECJ, ZUM-RD 2014, 613, para. 30 f. [20] BeckOK UrhR/Lauber-Rönsberg UrhG § 51a marginal no. 21. [21] Kreutzer, MMR 2022, 850 f.; Nordemann/Karsch/Fromm/Nordemann, Urheberrecht, § 51a UrhG, para. 25. [22] Cf. Kreutzer, MMR 2022, 851.[23] Birk, “Die Nutzung von Memes zu Webezwecken”, GRUR-Prax 2023, 321, 323.